Clinical Somatics. The exercises that have saved me a million times.

Reading time for this text: about 14 minutes.

Clinical Somatics. The exercises that have saved me a million times.

My life has always been characterized by a lot of movement and the associated sports injuries. Countless falls from my mountain bike in the 90s, finger capsule strains during handball lessons at sports university, severe shoulder and ankle traumas during gymnastics on the parallel bars and a protracted foot injury from capoeira training are just the tip of the iceberg and what I can remember spontaneously...

When I became self-employed as a trainer in the field of prevention around 2009 after completing my studies, something suddenly came into my life that I had never experienced before: I had back pain. Funnily enough, from today's perspective, it mainly occurred after giving my back pain prevention training sessions and was sometimes more, sometimes less present. However, my back pain were always there subliminally.

Lost in the jungle of therapies

Unfortunately, the movement tools and knowledge from my studies were of no real use to me. So, from then on, I was on the lookout. In search of methods that would help me to get my back pain under control. I went to masseurs, orthopedists and osteopaths, had physiotherapy, tested the method of a self-proclaimed pain specialist and had chiropractic. There I was pushed, pulled, injected, squared and twisted. The results of these therapies were sometimes better and sometimes worse. Sometimes they lasted shorter and sometimes longer. They relieved my pain for days or even just a few hours. However, this approach was not sustainable – at least in my individual case.

In my eyes, looking back, this was mainly due to one fact: I was always being treated, even though I kept saying that it was my back pain that I had ‘worked hard’ for over the years and that I wanted to take responsibility for it. (Note: Some of the methods mentioned are nowadays a bit more advanced and have incorporated active exercises, usually in the form of stretching exercises, into their program alongside passive treatments).

Of course, I also tested active methods and their effects on my back. First and foremost, strength training, which I have known well for many years, as well as classic gymnastic exercises, as you might find in many disciplines such as yoga, Pilates or spinal gymnastics. But here too, just like with strength and stretching exercises, the results were unfortunately only ‘okay’ and therefore anything but satisfactory for me.

At that time, I achieved the best results with banal, controlled and soft movement of joints. Even back then, people argued about whether these were mobility or flexibility exercises (or whatever) and discussed the difference between the various terms down to the last detail. I didn't really care and simply called it ‘movement of joints’ (slow, controlled and fluid movements through the whole range of motion of a joint). When training these exercises, a few principles emerged over time that proved to be useful and that I still teach in training sessions today.

Brain-friendly training. Light at the end of the tunnel?

It was probably around 2011 when I got to know Jutta Schäfer-Bossong from Darmstadt and took lessons with her in the Alexander Technique, a body-orientated method of perception and movement training developed by Australian actor Frederick Matthias Alexander. Body-orientated learning? What? At the time, I knew very little about the term, but I was interested, because one of the topics was about recognizing unfavorable movement habits and changing them on your own initiative. In contrast to the well-known competitive sports, the aspect of body and movement awareness suddenly emerged here. The slowness of a movement was consciously used as a training principle, which was reflected years later at a seminar I attended with Dragisa Jocic, a martial arts teacher from Bern, when he said: ‘If you do things too quickly, you lose the details.’ So I began to see everyday movements as training and to perform them slowly and consciously; I began to concentrate on the details, focusing on making the movements more efficient. And I felt the first real and lasting changes.

After being taught for some time by Jutta Schäfer-Bossong and also getting to know the better-known Feldenkrais Method in individual sessions, I finally became interested in another person: Dr Thomas Hanna, a trained religious philosopher who, fascinated by the human nervous system, took up a degree in neuropsychology and who was trained in Functional Integration, the Feldenkrais Method's individual lessons, from 1973 by the physicist, martial arts teacher and body therapist Moshé Feldenkrais.

A

friend of mine, a naturopath and osteopath himself, who I met at a kettlebell seminar and from whom I was able to learn a lot about trigger points, organized a weekend seminar on Hanna's work in Frankfurt am Main with my later mentor Martha Peterson: ‘The fundamentals of Hanna Somatic Education Intensive’. This is how I got to know the work of Dr Thomas Hanna ‘Hanna Somatic Education®’, a method that is also known under the non-proprietary name Clinical Somatics. The term Clinical Somatics also goes back to Thomas Hanna, who called his individual sessions ‘clinical sessions’.

A completely new field opened for me: where the Feldenkrais Method seemed too nebulous to me and in many aspects was too detailed and intangible, Thomas Hanna gave me a clear and comprehensible structure, which was important to me as a sports scientist. Where sports science was often too competitive for me, Hanna gave me deep insights into an area that I like to call ‘intelligent movement’ and created links to disciplines such as psychology, evolutionary biology, neuropsychology and philosophy.

I began to ask myself a lot of questions. Was it still simply about getting rid of my back pain? Or was it about nothing less than freedom? To be able to walk down the three steps in front of the house even at the age of 70? The three steps that connect me to the outside world. Was it about the freedom of still being able to regard the floor as a friend in old age and having less fear of falling? The freedom to be able to work with the functional complaints of my musculoskeletal system and no longer be helplessly at their mercy?

Thomas Hanna himself became my mentor, even though he died in a serious road accident in 1990. But the old audio recordings with his charming Texan accent accompanied me day after day for many years from then on – especially when my children still spent their afternoon naps in the baby carrier, and I spent an above-average amount of time going for walks.

The path with Hanna Somatics also must be travelled by yourself

I finally trained with Martha Peterson in the USA, Canada and Norway over three years, integrated the Clinical Somatics exercises into my life almost daily and refined the exercises. I did a lot of research on Thomas Hanna and exchanged letters and personal dialogue with people who knew Hanna and his work well from the past.

At that time, my work was very much characterized by individual Clinical Somatics sessions – mostly with people who suffered from back pain, shoulder and neck pain, but also from general joint stiffness or other functional complaints, mostly with the musculoskeletal system. But I had great problems with the classic therapist-patient relationship in this way of working. I saw myself as a teacher, but in the end I was ‘only’ seen by many as a therapist who was supposed to ‘take away’ pain in one to three individual sessions. The homework, the Clinical Somatics exercises, were often only half-heartedly implemented, or it was difficult to integrate them into everyday life. I only really realized this when a primary school teacher came to our second appointment and said: ‘Mr Schäfges, I must apologize. I haven't done my homework’. This way of working was neither sustainable nor really satisfying for me.

I work differently today. I now rarely have people with whom I work superficially in just a few appointments. Because the path with Hanna Somatics is also a path that you must take yourself. It requires a certain commitment and the will to learn and implement the method, to ‘play’ with it and adapt it to individual needs. For this reason, I now use Dr Thomas Hanna's method almost exclusively in the context of my personal training sessions. Here I work with people over long periods of time. I see some clients three times a week; others only every fortnight. But we are in close dialogue, we can discuss and tackle problems with implementation together, we can adapt and reinvent exercises and create an individual exercise plan. And above all, in a personal training context, there is a willingness to actively go the extra mile.

The theory behind this movement system

The technique behind the Clinical Somatics exercises can be compared quite well with progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) according to Dr. Edmund Jacobson, considering current neurobiological findings. In simple terms, the tension and relaxation phases involve slow, conscious tensing and controlled relaxation of muscles. Thomas Hanna used the term “pandiculation” for this. However, as pandiculation has a slightly different meaning, and not just in my eyes, I prefer to use the extended term “pandiculation according to Thomas Hanna”.

In contrast to the PMR approach of targeting individual muscles one after the other, Thomas Hanna's work is based on movement patterns, true to the motto “the brain doesn't know muscles, it only knows movements”. Hanna placed particular emphasis on three stress-related muscle reflexes, which were the focus of his work.

Also important for movement theory is the fact that the exercises are usually performed lying on the floor on the back, stomach or side. This allows us to focus entirely on the movement itself and on breathing. Furthermore, in these starting positions, gravity helps us to relax as we sink back to the floor. The more fully we lie on the floor at the end of the movement, the more relaxed we are and the more control we have regained.

The parallels with and influence on martial arts were also extremely exciting for me, as I learned about the principle of “relaxed punches” in the ancient Russian martial art Systema, which describes the positive effects of muscle relaxation on the intensity of a punch.

The science behind this movement system

Like the Neuroathletics Training in the field of sport or the Feldenkrais Method in the field of body-oriented learning, Hanna Somatics also focuses on the nervous system and aims to positively influence the “hardware” of the body (muscles, fascia, etc.) as well as other parameters such as physical performance or pain, by controlling the “software” (nervous system). Although the evidence regarding these methods is rather weak, they are fascinating and promising approaches for practice.

According to a recent report by the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare, a benefit of the Feldenkrais Method for limited mobility, has not yet been clearly established based on the scientific data available. However, there are indications of a benefit regarding Parkinson's disease and chronic lower back pain.

There is a very recent study on Hanna Somatics from the last quarter of 2022, which was published in the Saudi Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences. It is a retrospective study in which the influence of Hanna Somatics on neck pain and lower back pain was investigated. After each individual session, the pain level, painkiller consumption and visits to the doctor due to pain were recorded and documented for the study. The authors of the study found a significant positive influence of the method investigated on chronic spinal complaints, but also called for further studies to critically assess the techniques used, among other things.

It could now be presented as if this is scientific proof of the effectiveness of Hanna Somatics – which of course it is not. However, it is certainly a good start.

The movement practice

As it can be worthwhile in many cases to integrate the Clinical Somatics exercises into everyday life in one way or another, here are my instructions for two fundamental exercises “The Bow” (Arch & Release) and “Somatic Crunch” (Arch & Curl).

Soma Scan

According to Thomas Hanna, a soma is the body experienced from within. Without this ability to perceive our body, we would have a huge problem, because all organic processes are of a sensorimotor nature, i.e. they always involve the perception of a stimulus and the motor response to it. The Soma Scan is thus your before and after test instrument. Take a minute or two before the exercises to do this test to get to know your body and its patterns and do a before-and-after comparison after the exercises.

Exercise description

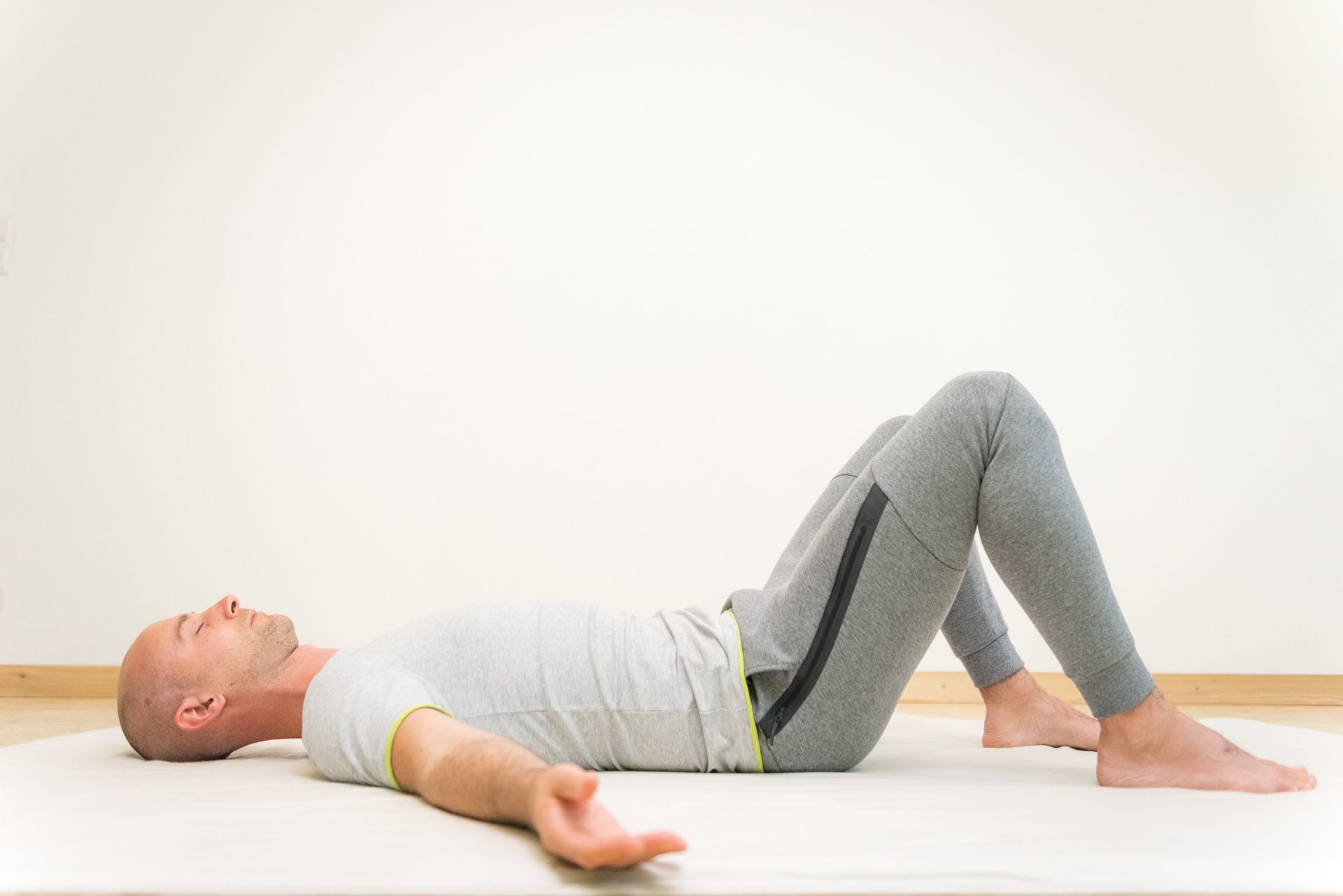

Lie on your back and listen to your body: How am I lying on the floor? Does my head fall into my neck? Do I need a pillow to lie comfortably? Are the backs of my shoulders lying loosely on the floor, or are they pointing clearly towards the ceiling? How is my breathing? Deep and relaxed, or rather chesty and shallow? How does my lower back feel? Is it very far from the floor, or is it almost touching the floor? If the former is the case, what effects does this position have? Can I leave my legs stretched out on the floor, or would I prefer to place my feet close to my buttocks to flatten and relieve the pressure on my lower back? How am I lying on the floor overall? Full, heavy, relaxed? Or selective and tense? Can I feel my own body weight on the floor? Or does even lying on the floor involve effort?

Other questions you can ask yourself after the exercise program:

How am I lying on the floor now? What has changed? You don't notice any difference? What could have caused this? How did you do the exercises? Hectic, in a hurry, carelessly? Do you feel a difference when you do the exercises calmly and mindfully? Perhaps you only notice a difference a few minutes later when you stand or walk after doing the exercises? What changes do you notice when you do the exercises regularly over a few weeks?

The Bow

Exercise description

The bow is the foundation of the Clinical Somatics exercises. Many other exercises can be derived from this one. And even if it seems trivial, it has already relaxed some back extensors and given the practitioner more control and therefore more strength and stability over large parts of the back muscles.

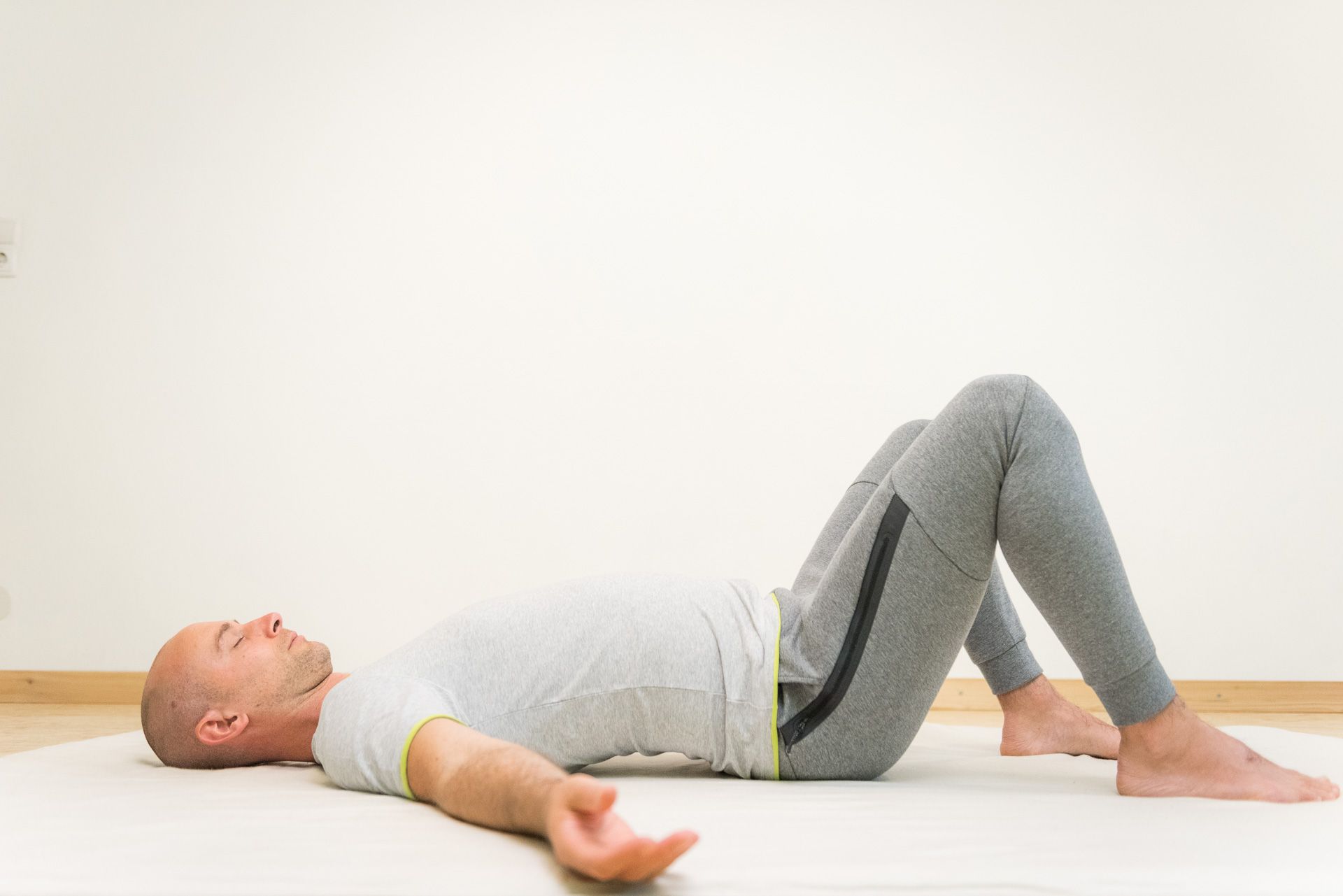

Photo 1: Start lying on your back with your feet on the floor close to your buttocks. Bring your awareness to the pelvis.

Photo 2: Breathe relaxed and freely into your stomach, and gently bend your torso. Gently arch your back and bring your lower back further away from the floor without your pelvis losing contact with the floor. Can you feel how your cervical spine flattens out in response to this movement? You can now intensify the tension on the back of your body by making a double chin and gently pressing the back of your head into the floor.

Photo 3: As you exhale, your back finally sinks back onto the mat in a controlled manner. Please do not force your back to the floor, but gradually reduce the tension and allow your back to sink to the floor. Your back muscles will feel longer and relax completely.

After each repetition, breathe in and out calmly one to three times, ideally through your nose, before starting the next repetition. Over time, get to know and appreciate the relaxing value of the breathing pause, the time between inhaling and exhaling vice versa.

If your back is sensitive and spasms easily, you can also perform this exercise with very small movements. The more sensitive you are, the slower, more conscious and more mindful you should be during the exercise. It is also possible to support your head with a small pillow if lying flat on the floor is uncomfortable.

Somatic Crunch

Exercise description

The Somatic Crunch is an extension of the Bow. A combined play between the back and front of your body. A back-and-forth movement between bending and stretching the spine. While the Bow ends when you sink back to the floor, in the Somatic Crunch you initiate the opposite movement and roll off the floor. One aim is to regain control of the abdominal muscles and back extensors and to rediscover a relaxed center so that you can stand upright more effortlessly, breathe better and, for example, rotate your upper body better in sports.

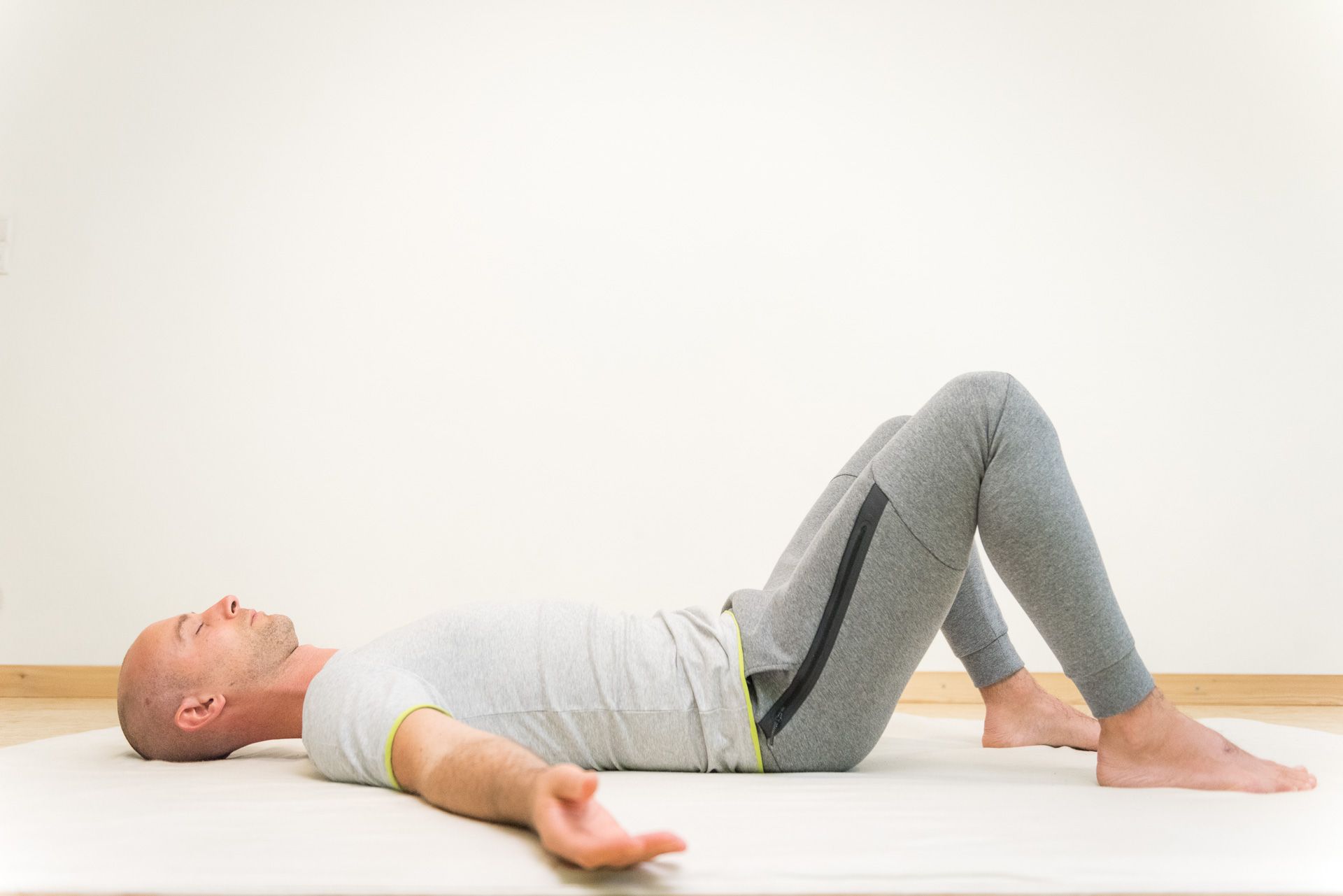

Photo 1: Start lying on your back with your feet on the floor close to your buttocks. Clasp your hands behind your head. Bring your awareness to the pelvis.

Photo 2: Breathe relaxed and freely into your stomach, and gently arch your torso. This will gently make you arch your back and bring your lower back further away from the floor without your pelvis losing contact with the floor. Can you feel how your cervical spine flattens out in response to this movement? You can now intensify the tension on the back of your body by making a double chin and gently pressing the back of your head into your clasped hands.

Photo 3: As you exhale, your back finally sinks back onto the mat in a controlled manner. Please do not force your back to the floor, but gradually reduce the tension and allow your back to sink to the floor. Your back muscles will feel longer and relax completely.

Photo 4: With the following exhalation, your abdominal muscles take over, your pelvis rolls back and pushes your lower back gently but clearly towards the floor. At the same time, your chin moves towards your chest and your head lifts, supported by your hands. The elbows now move towards each other. The rib cage pushes down towards the pelvis, causing the abdominal and intercostal muscles to tighten further. The elbows slowly move towards the knees. Can you feel how your back becomes longer and rounder as you gradually roll up and shorten the front? Please always remember that, despite a certain similarity, this exercise is not a fast performed ab crunch from gym.

Photo 5: As you inhale into your abdomen, slowly roll back to the starting position on the floor, vertebra by vertebra, and lower your head and elbows in a controlled manner. Make sure that your abdominal muscles are completely relaxed again.

After each repetition, breathe in and out calmly one to three times, ideally through your nose, before starting the next repetition. Over time, get to know and appreciate the relaxing value of the breathing pause, the time between inhaling and exhaling vice versa.

A training plan

- Soma Scan (test), 1–2 minutes.

- The Bow, at least 10 reps with 1–3 breaths between each repetition.

- Somatic Crunch, at least 10 reps, with 1–3 breaths between each repetition.

- Soma Scan (re-test), 1–2 minutes.

This short sequence is best used separately from strength training, sport-specific training, etc. It is best to do the exercises in the morning directly after getting up or in the evening before going to bed. The Clinical Somatics exercises can also be combined with a gentle movement routine on the floor with exercises such as cat-cow.

The field of application

There are many areas of application. However, I particularly recommend the Clinical Somatics exercises to

- Craftsperson or other professions with high physical workloads (constantly repetitive and/or one-sided workloads and high physical stress).

- People with traditional office jobs (too little movement and a lot of sitting, often coupled with high stress levels).

- People with back, shoulder or neck pain (especially those who have already had everything checked out medically and are at one's wits' end)

- Athletes (who want to work on themselves, their performance and old injuries on a functional level and are open to neuro-based methods).

- New parents who are often out and about with their baby in a baby carrier and are looking for a movement based counterbalance.

I personally still use the Clinical Somatics exercises. They saved me during the first few years with two small children, a time that was characterized by little sleep and long periods of carrying the children in baby slings, in my arms and on my shoulders. The exercises often saved me in my day-to-day DIY work when my ego and the load to be lifted were once again greater than my actual capacity. Many times, they gave me peace and relaxation after a hard day's work and ensured a restful night's sleep.

The Clinical Somatics exercises are certainly not an alternative to strength or sports-specific training (nor do they want to be). In addition, however, this exercise system plus the theoretical background are an excellent addition in the toolbox of trainers and therapists (like personal trainers, fitness trainers, athletic trainers, physiotherapists, orthopedists or therapists in the field of the body-oriented psychotherapy) as well as for athletes or “pain-ridden bodies” and so definitely worth a try.

– Thomas

References:

- Colshorn, Thomas (2020). Körperliche Power erfordert auch starke Nerven: Neuroathletik-Training in der Physiopraxis. In: Institut für Wissen in der Wirtschaft (Ausgabe 12/2020, Seite 16). https://www.iww.de/pp/praxisfuehrung/praxisangebot-koerperliche-power-erfordert-auch-starke-nerven-neuroathletik-training-in-der-physiopraxis-f133984 (Stand 28.02.2023).

- De Giorgi, Margherita: Shaping the Living Body: paradigms of soma and authority in Thomas Hanna’s writings (Seite 68). Brazilian Journal on Presence Studies, Porto Alegre. Band 5, Nummer 1, Seite 54–84, Jan./Apr. 2015.

- Derra, Claus (2017). Progressive Relaxation. Neurobiologische Grundlagen und Praxiswissen für Ärzte und Psychologen (2. Auflage, Seite 63ff). Springer-Verlag. Berlin.

- Hanna, Thomas (2016). Beweglich sein ein Leben lang. Die heilsame Wirkung von körperlicher Bewusstheit (17., durchgesehene und mit Farbfotos ausgestattete Neuausgabe). Kösel-Verlag. München.

- Hanna, Thomas: Clinical Somatic Education. A New Discipline in the Field of Health Care. In: Somatics, Magazine-Journal of the Bodily Arts and Sciences, Volume VIII, No. 1, Autumn/Winter 1990-91.

- Hanna, Thomas: Moshé Feldenkrais: The Silent Heritage. Somatics, Autumn/Winter 1984–85.

- Hanna, Thomas: Wave One Lectures CD #1 Intro. 1990. Minute 37:00.

- Heiduk, Robert (2013). Schreck lass nach. https://blog.eisenklinik.de/2013/04/02/schreck-lass-nach/ (Stand 28.02.2023).

- Huang, Qiuju & Babgi, Amani Ali (2022). Effect of Hanna Somatic Education on Low Back and Neck Pain Levels. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2022 Sep-Dec; 10(3):266-271. doi: 10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_580_21. Epub 2022 Sep 7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36247048/ (28.02.2023).

- Ingraham, Paul (2023). Pandiculation: nature's way of maintaining the functional integrity of the myofascial system? https://www.painscience.com/bibliography.php?bertolucci11 (Stand 28.02.2023).

- Ingraham, Paul (2023). Is pandiculation really about stretch? And other sexy updates. https://www.painscience.com/blog/is-pandiculation-really-about-stretch.html (Stand 28.02.2023).

- Ingraham, Paul (2023). Does pandiculation “reset” muscle tone? https://www.painscience.com/articles/pandiculation.php (Stand 28.02.2023).

- Ingraham, Paul (2023). Is pandiculation powerful? https://www.painscience.com/blog/is-pandiculation-powerful.html (Stand 28.02.2023).

- Institut für Wissen in der Wirtschaft (2020). IQWiG: Nutzen der Feldenkrais-Methode nach Datenlage unklar (Ausgabe 04/2022, Seite 1). https://www.iww.de/pp/perspektiven/studie-iqwig-nutzen-der-feldenkrais-methode-nach-datenlage-unklar-f143219 (Stand 28.02.2023)

- Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (2021). Störungen der Beweglichkeit. Hilft die Feldenkrais-Methode? https://www.iqwig.de/download/ht20-05_feldenkrais-methode-bei-stoerungen-der-beweglichkeit_vorlaeufiger-hta-bericht_v1-0.pdf (Stand 28.02.2023).

Note about affiliate links: Blog writing is fun, but also a big time commitment. You can support us in creating our blog posts by using the links marked with *. These are so-called affiliate links (this applies to a few, sometimes even to no links in the text). If you buy a product on the linked pages, we receive - without you having to pay more - a small commission. You profit from our article and product recommendations and we get a small commission. A win-win situation. Cool, isn't it?